2D Metroid Retrospective: A Hunter Rises - Article

by Paul Broussard , posted on 21 September 2021 / 3,266 ViewsMetroid, as a series, had kicked off with a bang, albeit one held back by some questionable design choices. Future generations would come to view Metroid 1 and 2 as important games, but heavily dated. Excellent ideas and innovative concepts, ultimately held back by flaws in a few key areas. They just needed one last push to move into the realm of all time classics.

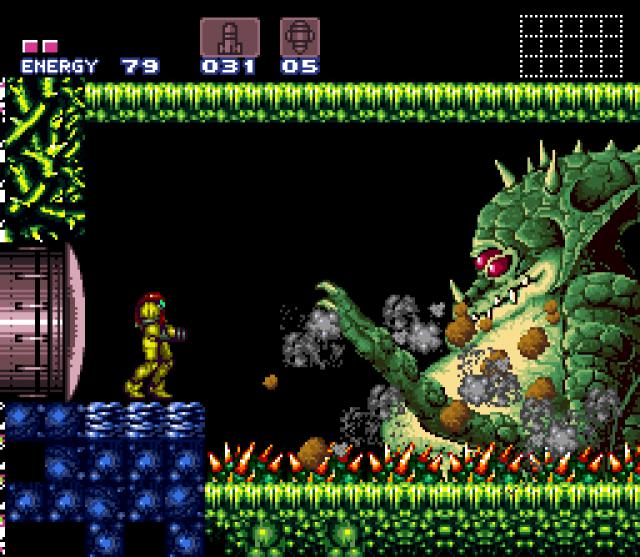

In 1994 they would get that push, with Super Metroid. Continuing the story from the prior two titles (it was something of a rarity in and of itself for Nintendo games to maintain a single continuity for three releases), Super Metroid sees Samus return to Planet Zebes to foil the Space Pirates' schemes one final time. While Metroid has always put more emphasis on the lore rather than the actual plot, the game’s final confrontation became one of the more powerful storytelling moments for 1990s gaming. The fact that the game manages to pull this off without any dialogue is even more impressive, and to this day it still remains a crucial lynchpin of the series' plot.

In many ways, Super Metroid’s general set-up echoes the same beats as the previous title, just bigger and better. Many of the same power-ups, areas, enemies, and bosses return, just vastly expanded upon and with a myriad of new acquisitions to supplement them. At the time, it was Nintendo’s biggest ever release, and this certainly shows; it’s packed with innovation. New items like the Speed Booster and Power Bomb would go on to become series staples, and other abilities like Wall Jumping and Shinesparking were first implemented into an exploration based game here before finding their way into other Metroidvanias.

Super Metroid excels at the series’ trademark senses of progression, isolation, and atmosphere. But what really sets Super Metroid apart, even from other titles in the series, is the game’s design. Super Metroid is simple, yet lends itself to a degree of complexity and player freedom that I would argue has yet to be surpassed. After exploring Zebes for a short while, players will stumble onto a room that contains nothing but a statue with four creatures. These creatures depict the four major bosses in the title. When a boss dies, the color drains from their portion of the statue. Defeat all four, and the statue crumbles, revealing the pathway to the last area of the game and the final boss.

Super Metroid, like other Metroid games, has an intended path for first time players to take, defeating the bosses from easiest to hardest. Virtually all first time players will follow this path; it’s at least initially hard to figure out how to get around the various obstacles in your way that prevent you from reaching other bosses early. But once you’ve been through the game once or twice, you start to see cracks in those obstacles. A spot that seemed like it required the high jump ability to reach before can actually be reached with a well-timed dash and a wall jump. Items that looked like they would require the Speed Booster can be obtained early with some manipulation of momentum and the Morph Ball. A gap that seemed like it needed the Grapple Beam to bypass can be overcome with clever use of Speed Booster.

And this is the genius behind Super Metroid; it sets up proverbial walls just high enough so that first time players are very unlikely to get past them and wind up stuck in a segment much tougher than what they were prepared for, yet not so high that veterans who are more familiar with the game’s mechanics can’t get over them. Super Metroid allows for an incredible degree of flexibility, but makes you earn it. Assuming you’re skilled enough, you can even go so far as to beat the four major bosses in reverse order, which means taking on later enemies without power-ups that would otherwise seem essential. You just need to be an extremely skilled player, who knows the game and Samus’ various skills inside and out.

Unsurprisingly, then, Super Metroid is an extremely popular title for speedrunning. Remarkably, all of this design comes without the need to really glitch or break the game at all. Unlikely many other popular speedrunning titles that rely heavily on clipping or taking the character of bounds to reach areas early, Super Metroid doesn’t really involve much of that at all. Super Metroid is, in short, a game that invites you to break it, but demands that you be skilled enough to do so.

All of this would be enough to earn Super Metroid very high marks if it released today. The fact that this was done in 1994, and holds up so well to this day, is a testament to how well built Super Metroid is. Super Metroid isn’t just revered for its ambition that other people built on and perfected later; it holds up spectacularly well on its own even in 2021. Sure, there are a few annoyances from SNES era game design. Space Jump is finicky, there are a few sizable leaps in logic you have to make to navigate the world on an initial playthrough, and the map isn’t the most intuitive or easy to read for first time players. But those are issues that modern day games still struggle with, and Super Metroid nails almost everything else perfectly.

Speaking of those modern day games, the list of titles chiefly inspired by Super Metroid reads like a veritable who’s who of landmark titles with an emphasis on exploration. Castlevania: Symphony of the Night? Heavily influenced by Super Metroid. Half Life’s level designers referred to Super Metroid frequently when building out their game. Played a Soulsborne title? Atmosphere and nonlinear design heavily draws on Super Metroid’s. Famous indie releases, like Ori and the Blind Forest, Hollow Knight, Axiom Verge, Guacamelee, and more? All owe a huge debt to Super Metroid.

Super Metroid is one of those games that I revere, and one I could easily dedicate an entire series of articles to in and of itself. However, that would take time away from the eventual sequel. It took eight years for another Metroid release to drop, and when it did, we got two. Despite eventually being overshadowed by the universally acclaimed Metroid Prime and the series' jump to 3D, Metroid Fusion was the direct sequel and story continuation for Super Metroid. So just how would Nintendo try to surpass one of the most influential games of all time?

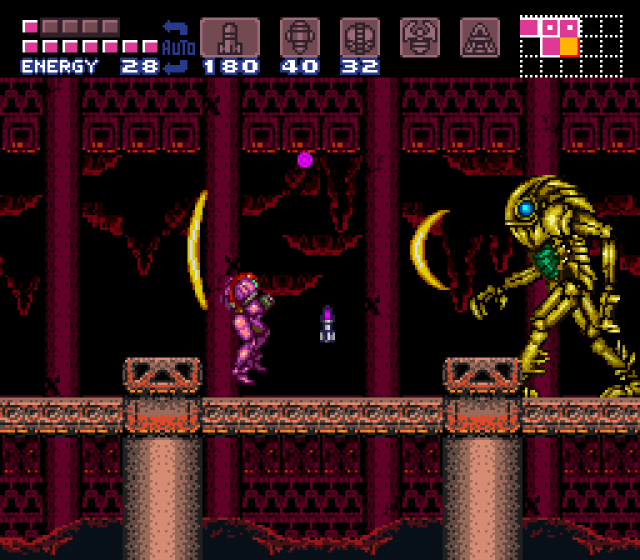

The answer was... Nintendo didn’t, really. Metroid Fusion took what was maybe the smart approach in hindsight, which was to recognize that Super was going to be extraordinarily difficult to top, and just gave up and did something else entirely. In contrast to Super’s very open-ended level design, with lots of opportunities for sequence breaking and experimentation, Fusion was a much more linear title with a heavier emphasis on plot and a much more rigid sense of progression.

Don’t get me wrong, though. Fusion is still very much a Metroid game. Exploration is still present, even if a bit more muted. The sense of gradually becoming more powerful and being able to slowly open up more of the world as you gain new items is still there, and the series’ trademark atmosphere plays more of a role than it ever has. In a way, Metroid Fusion feels like someone took a Metroid game and seasoned it with a horror title. It’s genuinely unnerving at times, in a way no other Metroid release (maybe no Metroidvania at all) has been.

The plot again revolves around Samus, who, after the events of Super Metroid, is working for the Galactic Federation again, protecting some soldiers on the same planet Metroid 2 took place on, SR-388. There, she finds herself attacked by the mysterious X parasite, which infects her central nervous system and nearly kills her. Turns out that the Metroids were actually the only known predators of the X parasite, and by wiping the Metroids out in Metroid 2, Samus and the Federation have unwittingly unleashed a seemingly indestructible parasite. This parasite can infect any organic creature simply by touching it and kills anyone it infects within hours. Oops.

Fortunately, Samus’ adventures from prior games left her with a sample of Metroid DNA on her armor, which someone from the Federation thoughtfully preserved and was able to manufacture into a vaccine. Being made from the DNA of a creature that possessed immunity to the X, the vaccine eradicates all traces of the X from Samus’ system, and now leaves her as the only being in the galaxy who is immune to X infection. She can even kill them by absorbing them... as weird as that sounds. With her newfound immunity, she is shipped to the BSL station above Planet SR-388, where the X has now spread.

After Samus arrives, it quickly becomes apparent that the X has the ability to not only infect any organic thing, but also to perfectly mimic the forms of its past hosts. Another thing that quickly becomes apparent is that the treatment that saved Samus’ life has some side effects, leaving her weakened and with a very notable vulnerability to cold, the greatest bane of Metroids. A weakness that could be exploited by, say, an X that happened to find infected remains of Samus’ Power Suit. An X parasite mimicking Samus Aran. And, since the real Samus now possesses the DNA of its only natural predator, it views her as its primary target.

This Samus Aran X, or SA-X as the game calls it, becomes one of the driving forces of the title’s horror themes. Throughout Samus’ exploration of the BSL, she will occasionally come across the SA-X. Unlike every other enemy the player has fought before in a Metroid entry, the SA-X cannot be killed. Of course it can’t; it’s mimicking Samus at full power, wielding an ice beam that can rip through the real Samus’ health bar. When the player comes across the SA-X, they have to hide or run; fighting will always result in a quick game over.

This mix of horror game-esque enemy design sprinkled into the traditional Metroid formula does a lot to make Fusion feel very unique, and very much like its own title, rather than Super Metroid 2. It’s surprisingly unnerving; while Fusion is far from the scariest game I’ve played, there’s just something about the way the SA-X acts, how it slowly patrols the environment, the very loud and deliberate footsteps, the occasional look at the camera, that just makes it feel eerie and unnatural. Kenji Yamamoto’s superb OST does a fantastic job of driving home how out of her depth Samus is now; the once mighty hunter forced to hide in a corner at times while she goes about her mission.

These SA-X segments are predetermined, which is probably at least part of the reasoning behind the more linear nature of the game. Having more control over when and where the player will enter certain rooms allows Fusion to pull off some very tense moments, such as one where the SA-X opens a door and walks over you right as you’re going through a morph ball tunnel underneath. The limits of the Gameboy Advance also probably played a role in what the team could realistically accomplish as far as an aggressive chasing entity goes.

For as creepy as the SA-X is, though, it isn’t perfect. The heavily scripted nature of things does mean that whatever scares are present initially are much less potent on repeat playthroughs. This becomes doubly apparent once the player realizes that the SA-X’s AI is as dumb as one could reasonably expect a space parasite to be. There are endless videos on YouTube of people exploiting the SA-X’s programming; making it run back in forth in place endlessly, shooting at a wall where Samus isn’t, jumping up and down furiously in a vain attempt to reach a ledge that the developers apparently didn’t expect Samus to be able to reach, etc. Somewhat thankfully, players are probably not very likely to discover this on an initial playthrough, but it does take the teeth out of repeat playthroughs.

When the SA-X is not on screen, it’s a more traditional Metroid affair. Samus navigates a series of areas, finds power-ups, and takes on a series of bosses. While the exploration has been scaled down a bit, and the list of power ups feature no new inclusions and are a bit underwhelming as a result, the bosses are probably the most complete and well-designed bunch of any 2D game. 2D Metroid titles have never exactly had incredibly complex combat systems, but Fusion manages to put together bosses that really force you to move quickly and think on your toes to survive.

That isn’t to say that Fusion manages to perfectly measure up to Super by doing something different. Even as well executed as the horror concepts and bosses in the game are, Fusion definitely lacks a lot of Super’s replayability and brilliant level design. That might be ok, in a way. Fusion was likely never going to be better than Super by simply trying to imitate it, and instead it comes out as a very unique title that avoids many of those comparisons.

If you’ve paid attention to the trailers for Metroid Dread, you may have noticed a number of similarities between the concept of the SA-X in Fusion and the EMMI units present in Dread. This is no coincidence; Yoshio Sakamoto, developer for nearly all of the 2D Metroid titles (Fusion and Dread included) has noted that the EMMI are, in large part, an extension of the SA-X design from Fusion. Dread builds off the concept of Samus being chased by an entity, but appears to be expanding it, with larger areas for encounters to organically happen and a much greater onus on the player to stay out of sight. Hopefully, the EMMI will end up being to the SA-X what Super Metroid was to Metroid; taking a general concept and expanding it to become something bigger and better.

In many ways, if you’re looking to play just one Metroid release before Dread, Fusion may be the best one. Not only does Fusion directly precede Dread in the timeline, the general feel of the SA-X will likely prepare you well for handling the EMMI robots. But this begs the question: if Fusion is the last game in the timeline before Dread, what are the other two 2D games we haven’t covered yet? To learn about those, we have to venture into Nintendo’s old comfort zone... the remakes.

More Articles

Great Article, these 2 games are very important and amazing. I do not agree that they have aged as i enjoy these every time i play them.

Good read. I'm so happy Metroid is finally giving it's moment. Dread will sell well and Prime 4 will only push the franchise forward. Can't wait.

That was a good read.

Their artstyles have held up nicely.

A little late to comment, I know, sorry, but wanted to say that I enjoyed reading this article! The commentary on Metroid Fusion especially really captures its unique kind of appeal that Dread's primarily building off of, it would very much appear. Released the same year as the original Metroid Prime, it in a way seemed appropriate for the handheld entry to represent a change in direction the same as the franchise's well-loved shift to 3D on the GameCube.

At the same time though, I can't help selfishly wishing that Super Metroid had gotten the bulk of the commentary here because, in my view anyway, it's not only the overall best Metroid game, but also one of the very best video games ever made, period. You captured some of the reasons here in discussing how the developers made playing and replaying the game into a kind of art form all its own, and that that they did so on purpose (unlike with so many other games). But it's more than that. Those who've followed my posts will know how I often cite the 1920s (along with the '70s) as my favorite eras in film-making and you may gather my love of silent movies from that. There's a whoooooooole art to crafting a compelling story relying primarily on music and atmosphere instead of dialogue. Super Metroid is like that for me: to me, playing Super Metroid is like participating in a silent movie. A really good one. And that was precisely the intention!

It's so difficult to really put the ambience of Super Metroid into words. Unlike in earlier Metroid games, it's primarily a spooky, downbeat kind of soundtrack, and it's not like generally in-your-face aggressive either save for boss fights for obvious reasons. Rather, there's a legitimate sense of build-up that's captured mostly in a prevailing subdued aura of menace, or sometimes even just creepy silence, and it sort of mirrors the game's shift away from relying on the standard upbeat, cutesy vibe we associate with the Nintendo brand. That shift makes sense in a lot of ways in terms of its timing in that, you know, Donkey Kong Country (borrowing aesthetically from Sonic the Hedgehog in terms of slightly edgier protagonists with more stylization and such) was released later that same year and the original Star Fox had come out just shortly before . Losing to Sega in the home console market at the time, these things were part of a period where Nintendo sought to regain the loyalty of some now-older fans from the NES era that they'd lost to Sega's Genesis, which was regarded as geared more toward tweens and teens than younger children. I'd become primarily a Sega gamer by that time myself (well and a 3DO gamer, but that's another story) and part of this target market. The soundtrack was a HUGE aspect of that!

Another, related thing was the visuals. Up to that point, I don't think I'd ever seen backgrounds that were quite so detailed and animated before and, together with the background music and the ways it transitioned from one interconnected setting to another, it just set a mood like no other game I'd ever played up to that point. It made the world feel alive and drove home the feeling of isolation EXCEEDINGLY well! If you spend as much time alone as I do, you know it can get to be a quietly unnerving feeling in just this sort of way. And it makes discovering something like the ability to blow up a tunnel to progress feel not only kind of revolutionary in principle, but also downright viscerally satisfying.

But what truly makes Super Metroid extra special to me beyond all of these things is its ending. It just concentrates a life lesson I've learned over and over again and it manages to do so without the use of dialogue. It's..just..perfect. To this day, it still makes me tear up. The game doesn't beat you over the head with its message, but that's because it doesn't have to. Such is the strength of its design.

Well that's all really. I just had to add a few ruminations on my favorite Metroid game (to say nothing of my favorite metroid). Okay okay, it's basically the original Metroid again, but radically expanded and improved, true. But the details here make a WORLD of difference. Literally. They make the game's world feel almost entirely different. It's scarcely aged at all for me. The uniquely Super NES, 24-meg vibe has only grown more nostalgic and appealing for me with age.

(Also, side note here, Super Metroid has my favorite character model for Samus too. Is that weird? Does it mean I'm old?)

Essay Pro

Essay Pro