Critiquing Shin Megami Tensei IV: Apocalypse - Article

by Spencer Manigat , posted on 29 December 2016 / 13,948 Views

A few months ago, I reviewed Tokyo Mirage Sessions #FE, the pop-idol crossover JRPG between Atlus' Shin Megami Tensei series and Nintendo's Fire Emblem series. In it, I mentioned that the only entry I'd ever played of the former was Shin Megami Tensei IV, bringing up the fact that I enjoyed it quite a lot. That all changed this September when I received a copy of its pseudo-sequel, Shin Megami Tensei IV: Apocalypse, from its publisher for review, and I have to say that finishing it left me extremely disappointed.

Before starting, I'd like to emphasize that while this is based off of a review copy, this is not a review of the game, but a critique of it. As such, I'll be focusing almost exclusively on things that I found disagreeable, while giving not much more than a cursory reference or two to elements that I actually enjoyed. I also must mention that there will be SPOILERS for the entirety of both Shin Megami Tensei IV: Apocalypse and the original Shin Megami Tensei IV, so if you haven't already, I'd strongly recommend finishing both games first before reading.

Chronologically, Apocalypse takes place on a divergent timeline, somewhere near the end of the previous game's Neutral path. It follows the story of the player character Nanashi and his childhood friend Asahi, two demon hunters in training, as they struggle to make a name for themselves in a war-torn Tokyo. Rather than a war of nations, Tokyo finds itself battleground to a war of the realms - a war between Merkabah and Lucifer, angels and demons, heaven and hell.

There are two major story beats where Apocalypse's timeline diverges from the previous game. The events of the first beat are inextricably tied to the events of the second. The first is with the death and resurrection of Nanashi. Near the beginning of the game, Nanashi and his two demon hunter mentors are slaughtered by a demon called Adramelech. Dagda, the supreme "Good God" of Celtic myth, meets Nanashi in the underworld and offers him a second chance at life in exchange for one thing: his servitude. Nanashi is to become his Godslayer and help Dagda achieve his goal of committing mass deicide and creating a new universe where all life is one with nature and "devoid of all bonds," apparently. The second is when Nanashi releases the seal that imprisons Krishna, Apocalypse's main baddie, which really sets Apocalypse's timeline into full divergence.

One of my core issues with Apocalypse is that Dagda is an unlikable prick, and remains so throughout the duration of the game. This wouldn't be a problem if not for Dagda's integral role as a narrative and mechanical force meant to persuade the player to "sever their bonds" and go down one of the game's two major moral routes. Dagda doesn't give Nanashi any compelling reasons to agree with his point of view, though. All he does is sit in his little smartphone box and blankly complain about how bonds hold people back, all while the story is doing absolutely everything in its power to argue against that.

This includes giving Dagda by far the least amount of screen time of any of the major characters, even though he is arguably the most important one. In a lot of ways, Dagda is presented as this game's analog to Burroughs from the last. In the previous game, Burroughs would pop up constantly. Whether it was to congratulate Flynn for completing a mission, to brag about him to other Burroughs, or to reprimand him for being indecisive, she was always a constant presence in that game. Dagda has no such presence, even though he plays a far more vital role in the plot than she was ever intended to.

Dagda's line of thinking is also completely at odds with his actions. He criticizes other gods for using human beings as mere chess pieces towards their own selfish ends, all while using Nanashi as a puppet for his own goals. He chides with contempt whenever any character shows even the slightest sign of dependency on others, all the while constantly depending on Nanashi himself. He argues in favor of severing bonds, all while forming a bond with Nanashi that persists even when he ultimately achieves his goal. At best, Dagda is a walking contradiction, but at worst he's a critical impediment to the goals and aspirations that Apocalypse strives, but ultimately fails, to achieve.

Dagda can't be blamed for everything though, because as I said before, the story does everything in its power to work against him by pushing the most sugary narrative of peace and comradery I assume the mainline series has ever seen. The execution of the focus on bonds and companionship on the whole feels very foreign from what I had always assumed were the intended aspirations of mainline Shin Megami Tensei as a franchise. I think it's because this game focuses more on the characters and how they interact with each other, while the previous games focused more on ideas and how they impact people's lives.

My point is that, in Apocalypse, your party members have no reason to exist from a narrative perspective outside of just being Nanashi's companions. They aren't each embodying separate narrative themes or ideas that the story is trying to discuss or explore.

In the previous game, Walter existed to embody a philosophy where the strong rule and the weak are ruled upon. Jonathan represented a desire for order amongst ensuing chaos. Now both of these were taken to their absolute worst extremes, and I don't think that either of them are examples of a good way to execute this, but what I'm trying to say is that neither Walter nor Jonathan actually needed to be Flynn's companion for their existence in the story of that game to have had meaning or purpose.

A FOCUS ON FRIENDSHIP

Friendship was used then as a vehicle to explore the themes they represented, while in Apocalypse, friendship itself is the theme that every party member represents. There are no real complexities in any of the relationships because every character completely abandons their prior allegiances and values, no matter how deeply ingrained, to join Nanashi and Asahi's random band of misfits by the end. I cannot overstate enough just how much of an issue this is. The theme of Apocalypse is "making or breaking" bonds, not just making them. Because of the way that Nanashi's friends are presented within the context of the story, the Peace vs. Anarchy angle doesn't work as a functional morality system.

Much is made adieu about the thoughtfulness of the morality systems in mainline Shin Megami Tensei games, but of the two that I've played so far, both have fallen completely flat on their faces in executing them in a compelling way, and both for very similar and very different reasons. Even so, Apocalypse does the seemingly impossible task of doing morality even worse than its predecessor.

The first thing to make abundantly clear is that the two main paths in the game are in absolutely no way "Neutral" paths like was advertised. Peace is the sugary-sweet good path while Anarchy is the "I'm a monster" evil path. There is no semblance of nuance with the morality here. If you're making the choices you'd make in real life, and you're not a heartless sociopath, you'll get the Peace ending. If you're making choices because you're curious and want to see the Anarchy ending, you'll get the Anarchy ending.

Apocalypse isn't trying to say something with its morality. It isn't trying to challenge your values and it isn't trying to make you think. The issue is that challenging a player's values is the only real value that morality systems have in video games in the first place. If they aren't making you think, they fail to be functional morality systems, and that's exactly what's happened here. In order to go down the Anarchy route, Nanashi has to literally become just as unlikable a prick as Dagda. The game does absolutely nothing to make Anarchy actually seem like a justifiable or at least "necessary evil" choice. If you're decent, choose Peace. If you're curious, choose Anarchy. That's all it boils down to. With how the game treats morality, Peace gets to have its cake and eat it too, while Anarchy has no cake and doesn't even know what one looks like.

Even if you absolutely hate every party member in the game, none of them actually give Nanashi any compelling reason to treat them as poorly as he must to earn Anarchy alignment points. What could have actually been more compelling is if each of the characters had to work together against their wills from beginning to end to reach a common end. In this scenario, the "bond" which connects them wouldn't be friendship, but a shared goal: "to survive" or something like that. Apocalypse could've then had each character commit a massive act of betrayal that acts to set the group back, and the player has to then decide whether to maintain their strained bond or sever it forever.

MORE COMPLICATED RELATIONSHIPS

Each character is already driven by their previous alliances, so making something like this believable, sympathetic, and true to their characters would write itself. Asahi would be driven by vengeance over the deaths of her mentors and later her father. Nozomi would be dedicated to her commitment to protect the fairies and her allegiance to Nanu. Hallelujah would be committed to the Ashura-Kai, Toki to the Ring of Gaia, and Gaston to Mikado. Isabeau would be committed to protecting Flynn, and the little green intruder just wouldn't exist. It's their alliances to their previous factions which would cause them to "sever bonds" with the group in the way that Dagda wants Nanashi to sever his bonds with them.

Apocalypse could've even presented different points in the game where each companion was destined to die horrifically unless the player did something which went against their values. Basically, multiple "for the greater good" scenarios. The game could have some characters commit their acts of betrayal before the "death choice," while others would commit their act of betrayal only after they've been saved/spared. This would've made Nanashi's relationships with the various party members complicated, making the matter of severing bonds with them throughout the game far more grey.

The point is to make the player think and give the game some much needed nuance. If this game's main theme is bonds, and this is a mainline Shin Megami Tensei game, then it should be doing everything in its power to put stress on those bonds and reveal the uncomfortable realities that come with forging them. Doing anything otherwise is far too convenient and serves to undermine the entire game.

Speaking of convenience, something that Apocalypse has been universally praised for are its plethora of quality of life improvements over Shin Megami Tensei IV and the rest of the franchise in general. While most of the improvements were welcome and make this entry the most polished in the series, I think that they go a bit overboard with many of them. One such improvement over the previous games is that Apocalypse highlights rooms which have NPCs with new dialog by giving those rooms a glowing yellow dialog bubble.

This is incredibly convenient, and helps exploration feel more focused - great. The problem, however, is that these dialog bubbles are placed on the bottom screen, meaning that players are incentivized to keep their eyes glued to the map instead focusing on the actual world. This is also partially why I don't like that there's no option to turn off the map entirely. Because the map also draws itself in real time, the player is incentivized to stare at the map even more for an idea of where to go next instead of establishing an actual sense of place within the world and familiarizing themselves with the landmarks of the area they're currently in.

It's a shame because both Apocalypse and the original Shin Megami Tensei IV have excellent dungeon design in that the world itself feels like one organically interconnected dungeon. Every area feels like a place that was once lived in, but is now decrepit, and that tacitly fleshes out Tokyo far beyond what any dialog or story moment could ever hope to convey explicitly. Placing those yellow speech bubble highlights in the world itself, on top of removing the world map from the default bottom screen, would've made traversing Tokyo less convenient, but it also would've forced players to survey their environments more and stay immersed in the setting, rather than just keeping their eyes fixated on the map the whole time.

DEMONS IN THE OVERWORLD

Another way by which Apocalypse places more importance on convenience than on player immersion is with demon encounters in the overworld. In Shin Megami Tensei IV, walking about the overworld used to be tense because demons would constantly aggro and try to attack you. Sometimes, just seeing one would freeze you up and keep you cautious and mindful about how you'd move about so as to not let them notice you. Compounded with the punishing difficulty that these games fame themselves on, it made for a truly compelling experience.

Now, most demons won't attack Nanashi unless he engages with them first, even when they're standing right next to him and staring right at him. This makes Tokyo feel like a much more hospitable place to travel than in the previous game because demons in the overworld are much more docile. This is in stark contrast to the narrative being told, where the people of Tokyo are literally too petrified to even walk outside. If only they knew how friendly these guys really are.

Apocalypse's alignment mechanic has also become a casualty of unnecessary mechanical streamlining. Shin Megami Tensei IV's point-based alignment system was something I absolutely hated in that game, but it was because of how it was executed. Choices that would ultimately effect which ending you'd get was blatantly telegraphed to the player, not only with a condescending "Choice!" icon, but with Walter and Jonathan constantly butting in to patronizingly telegraph which alignment each choice would steer you towards.

IF IT'S BROKE, THROW IT AWAY?

The alignment system had no subtlety, that was my problem with it, but rather than actually fixing that lack of subtlety, Apocalypse instead chooses drain it of all its meaning and impact completely. Absolutely nothing you do in Apocalypse holds any meaningful consequence, because you simply get to choose which ending you get of your own volition. You're only penalized if your choice goes against your alignment, and all it does is cause Nanashi to lose items or demons. It's an annoying inconvenience, rather than a thought provoking consequence.

It doesn't stop there, though. Apocalypse also sees the return of Healing Springs, a mechanic from Nocturne. Again, while convenient, they serve to give lower stakes to traversing Tokyo, and makes the whole ordeal less tense. I'm actually not against something like this in theory, but the implementation and execution of it here evaporates any sense of threat or menace that the overworld had left. In combination with more hostile demons, the presence of Healing Springs could have created a great juxtaposition between the tension of traveling such a dangerous and unforgiving world and the relief of shelter. Instead, they simply serve as a way to make traversing through the world that extra bit more convenient.

I'd like to take a moment now to speak on something that's been heavy on my mind for quite a while. It's on the topic of an idea I'd like to call "franchise authenticity." We're all attracted to certain games for certain reasons, and those elements that attract us can cause us to anticipate future iterations in that series of games. It's what turns us into fans. From game to game in a given franchise, some of those elements can change or be spun on its head, but as long as those core elements remain faithful to what initially pulled you in, you're likely to derive at least a little enjoyment out of it.

What I've been thinking about lately is what those core elements are in any given franchise. Who decides what those elements get to be? What happens when a game in that franchise does away with those core elements to create something new? Does it matter? Is it still a part of that franchise if it doesn't?

If we're going to be adults about this, the final answer has to be yes, but I don't think that this means that we can't criticize it. I believe that, as being part of a series, there are certain core elements that must be revered and understood. Any game that does otherwise isn't being authentic to the values of the franchise, and should be criticized as such. That's where this term "franchise authenticity" comes from.

A good, relevant example of this is the recently released Metroid Prime: Federation Force for the 3DS. A lot of fans were upset because, while the game walks like a Metroid game and talks like a Metroid game, it misses the core elements that make it feel like a Metroid game. For Metroid, those elements are exploration, isolation, and a growing sense of power as the game progresses.

The worry is not so much that these elements exist within the vacuum that is Federation Force, but that some franchise-inauthentic elements could make their way into a mainline Metroid game, whether it's another Prime game or 2D Metroid. It's a worry I echoed myself when I argued that it was actually Prime itself that began to feel as though it lacked some franchise authenticity. The problem with Prime, however, was that it was still a good game. It appropriately founded its own fanbase that felt that it was the foundation by which the authenticity of all other games in the franchise would be compared to.

I asked before who gets to decide what those elements get to be, and I want so desperately to be able to say that it’s the first landmark game in any given series that does because that's what I personally believe, but the truth is that that's not the case. The fact of the matter is that it's actually fans, as a collective, who get to decide when a game is being franchise authentic, which is why the existence and apparent critical success of Shin Megami Tensei IV: Apocalypse terrifies me so much. Because, no matter what I say in this critique, I cannot bring myself to say that it's not an enjoyable game. That is despite its flaws. My biggest issue with it is that it's an incredibly franchise-inauthentic game, but in a few years, me and fans like me won't be the ones who get to decide that, which means that games like this could be what the mainline Shin Megami Tensei games look like going forward.

There are many definitions of the word "macabre," but perhaps my favorite one describes it as "dwelling on the gruesome." To me, that is at the heart of mainline Shin Megami Tensei's essence. That's what makes any given game in the series franchise authentic, and that's what initially drew me to Shin Megami Tensei IV. Everything that game did, every theme it presented, was in pursuit of making the player dwell on the gruesome, and it's what makes me want to go back and play all of the other games in the series. I'm currently playing through and loving the iOS localization of the first Shin Megami Tensei, in case you're curious.

To be clear, "dwelling on the gruesome" could mean anything from "dwelling on" a violent death, a horrific truth, an unfavorable decision, or an unfortunate outcome. The operative word here is "dwell," though. The macabre isn't so fixating because it presents you with uncomfortable situations, but because it forces you to contemplate them.

MACABRE VS. EDGE

MACABRE VS. EDGE

On the other hand, there's "edge." Webster defines edge as having a bold, provocative, or unconventional quality. The important distinction to consider here is that edge is more concerned about how its quality is perceived. That describes almost every semblance of the darker themes that appear in Apocalypse. It's more concerned about looking macabre than actually being macabre. That's why it feels so inauthentic.

Asahi wasn't killed later in the game because Atlus wanted players to think about the loss of a long-traveled companion - if they did, they wouldn't have revived her in the Peace route, the only route where players would've actually cared that she died. They did it because it makes Shesha look cruel and because it makes Apocalypse look unforgiving. Edge is more concerned about how things appear than how they truly are. Macabre is concerned about forcing you to think about how unpleasant reality truly can be.

Nikkari and Manabu too. They didn't die early on because Apocalypse wanted the player to contemplate death or the harsh realities of weakness, they died because the developers wanted to make Tokyo look unrelenting. They were purely a plot device meant to give Tokyo the aesthetic of menace without needing to give it any of the feel. That's why I didn't mention them by name in the beginning of this critique when I brought them up. I genuinely didn't remember what their names were because I genuinely have trouble remembering that they were even a part of the game. Without substance, they served as little more than unmemorable plot devices.

CONTEXT IS PARAMOUNT

You know who I do remember, though? Issachar, from the original game. Arguably more of a shameless plot device than Nikkari and Manabu were, Issachar was also killed off at the beginning of his game with very little time to get to know or like him. And yet he was infinitely more memorable. Why is that? Well it's context, of course. Issachar’s death was contextualized by two things: the element of classism between the Luxurors and the Filthy Casuals of Mikado, and the final decision of whether to finish him off or spare him after he chose to become a demon. Even ignoring Walter and Jonathan's intrusive banter, which completely ruined the mood and gravity of the fight, choosing to finish Issachar off to end his suffering is a decision I still think about because the morality of it is ambiguous. There are plenty of demons in the Shin Megami Tensei universe who aren't evil - who don't suffer. How do I know that there was really no hope for him to become the same way? How do I know that he couldn't be helped?

Well the answers to those questions don't matter because the point is that I'm actually asking questions. Shin Megami Tensei IV got me to dwell on Issachar's death, and that's what it means to be macabre. In that moment, Shin Megami Tensei IV succeeded where Apocalypse all too often fails. I want to be clear, though. What I'm criticizing here is not execution, but ambition. I'm not criticizing Apocalypse's execution of being edgy; it's of no concern to me if it's doing edge well. In fact, I think that it actually does do edge well, and for another franchise or a further removed spin off, I might actually enjoy that more. What I'm concerned about is its desire to be edgy at all, instead of macabre. I'm concerned because I'm suspicious that Atlus genuinely believed that they were aspiring to be macabre, and don't actually understand the difference anymore.

Or maybe they just don't trust the average Shin Megami Tensei fan with the stakes needed to properly pull off the macabre anymore. Look no further than Asahi's revival along the Peace route. That was the moment where everything about this game clicked for me, because I knew it would happen. As soon as Shesha murdered Asahi, after I recovered from my initial shock, the first thing I thought was how they better not do some power-of-friendship nonsense at the end and bring her back. But they did, rendering the entire ordeal meaningless. It's the cheapest way to garner an emotional response from your audience and makes every decision the player makes ring hollow, all because the game didn't have the balls to keep her dead.

Shin Megami Tensei IV: Apocalypse has no teeth. It's a pit bull pup trying to act like a full-grown dog, while having absolutely no understanding of what that actually entails. Looking at Nikkari and Manabu again, there was little risk of upsetting players too much by killing them off because we hardly got to know them before it happened. On top of that, Asahi seems to shake it off almost entirely, remaining bloomingly optimistic throughout most of their adventure. Now I'm not about to go too hard on Asahi's characterization since actually I really like her, but her mentors only recently passed away and she was back to being silly and cheery the very next day.

There's absolutely nothing wrong with having levity, even in a franchise as macabre as mainline Shin Megami Tensei, but the balance needs to be perfect so as to not deflate tension and jeopardize the integrity of what's supposed to be at stake. Too little, and the game will begin to feel emotionally exhausting. Too much of it, though, and it begins to feel like the characters don't take the situations they find themselves in as seriously as the player is expected to. The whole love triangle subplot between Nanashi, Asahi, and Toki is a relevant example of far too much levity.

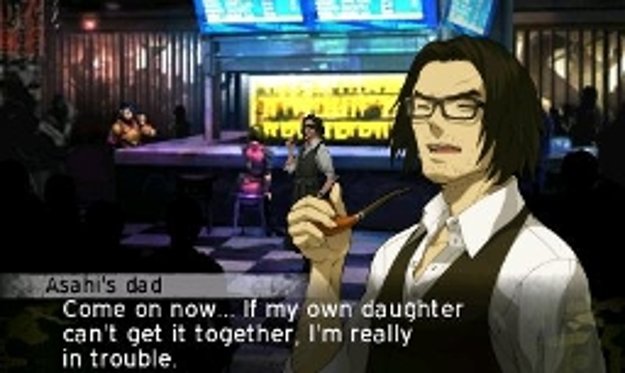

It was clearly added for comic relief, and perhaps a bit of fanservice as well, but it just obliterates all sense that anything is at stake when the world is literally ending for the second time and these two are bickering over who will get to bone Nanashi when they're all 18 and of legal consenting age. Asahi's romantic interest in Nanashi also has the unintended effect of making her father's death less meaningful to the player than it potentially could have been otherwise. Allow me to explain.

Throughout the game, Nanashi's reminded that he grew up with Asahi and her father. It's strongly implied that he looks at her father as a father figure for himself as well. I initially assumed that this would mean that Asahi's relationship with Nanashi would be more similar to a step sister, only that can't be the case because Asahi very clearly doesn't look at or treat him like a brother. She treats him as a love interest, so it can at least be inferred that the relationship they have with each other is not familial. It would make no sense for Nanashi to look at Asahi's father familially, but not Asahi. Going by how Asahi treats Nanashi, the relationship between him and her father likely doesn't go too far past him merely providing food and shelter for the friend of his daughter.

This obviously doesn't mean that his death becomes meaningless to Nanashi, but the death of a friend's father is never going to hit as close to home as someone that Nanashi viewed as a father figure himself. It takes something that was likely intended to be impactful for both Asahi and Nanashi equally, and turns it into a character beat for Asahi almost exclusively. All because the writers wanted some harem humor.

There's been a bit of an elephant in the room that I've tried to avoid bringing up too early in this critique because I wanted to discuss every disagreeable facet of the game thoroughly before talking about what is perhaps the most controversial and divisive one. I wanted to make sure that I covered all of my bases in painstaking detail to avoid being accused of anything unfair. I hinted at this a little bit when I spoke on the element of "franchise authenticity," but I'm going to go into it in depth now, because to ignore it would be dishonest and irresponsible.

I'm sure that more than a few of you have noticed my careful wording when making generalizations about the Shin Megami Tensei franchise. "Mainline" Shin Megami Tensei is how I've tried to phrase it, and I'm sure that most fans can tell why. There's a bit of an uncomfortable rift within the fanbase of this series and, while the games that are excluded from the "mainline" tag are both plentiful and diverse, most fans know that when you "mainline Shin Megami Tensei," what you're really trying to say is "not post-Persona 3/4 Megami Tensei."

I'm about to start playing Persona 3 on a friend's borrowed PSP. I've watched and enjoyed both Persona 4 anime adaptations. I've played Persona 4 Arena Ultimax and mopped my friend with my main Teddie, and I'm literally giddy with anticipation of finally getting to play Persona 5. I'm anything but a Persona hater, but Persona serves as a sort of balance of powers when it comes to Shin Megami Tensei, and it has a lane.

I mentioned this in the Tokyo Mirage Sessions #FE review that I brought up earlier. Here's what I said:

"If the mainline Shin Megami Tensei games are bleak and dreary, while the Persona (as well as other) spin-offs have leaned a little more in the middle, then Tokyo Mirage Sessions #FE sits comfortable at the sweetest end of the spectrum."

I called this balance of tone in Shin Megami Tensei games a sort of trichotomy. Persona has its place in the Shin Megami Tensei franchise that cannot be denied, but there was a moment of awakening for me when playing through Apocalypse. A moment when I knew that a traditional review wouldn't be appropriate for a game like this because its issues are far too complicated for a simple recommendation assessment. I was playing the game for review, and was getting frustrated with the characters. I liked them, but I felt like they weren't being fleshed out nearly enough, and was trying to figure out how they could've solved this apparent issue.

![]()

Then I thought back to my playthrough of Tokyo Mirage Sessions #FE, and the answer seemed obvious. What this game needed was a social link system like that game had! Then I remembered that this was a "mainline" Shin Megami Tensei game, not Tokyo Mirage Sessions #FE and not Persona, and got a chill.

Nanashi, Asahi, Hallelujah, Navarre, Gaston, Toki, Nozomi, Isabeau.

All of these characters, outside of maybe Isabeau, follow relatively straight-forward archetypes, and I honestly don't have a problem with that. People can relate to archetypes because they're simple and broad. As long as the characters are likable, I think that they'll have done their job to at least some degree. There's not a character here that I dislike. Not even Navarre. But let's look at the playable cast of Persona 4 for a moment. Please take note of the order I'm putting them in and compare.

Yu, Chie, Yosuke, Teddie, Kanji, Naoto, Rise, Yukiko.

The main character, the energetic leading girl, the laid-back guy, the mascot, the guy with a tough exterior but a heart of gold, the enigma, the eye candy, and the reserved one. None of these comparisons are exact, but few can deny that there is at least something uncanny about the comparison I just drew. People who communicated disdain for Persona as a sub-series did it because they were afraid that its immense and eclipsing popularity would lead to something like this to happening, and it finally did.

I love that Persona exists and that it has a fanbase of passionate enthusiasts that eat it up, but there was always a place for mainline Shin Megami Tensei too. Even if it was eclipsed in popularity and even if it has become destined to play second fiddle to Persona, there's always been a place for people to go who specifically liked what only mainline Shin Megami Tensei could offer, and now it feels like that's in jeopardy. This is just one game, I know, but this wasn't made by some spun off team. Studio Maniax themselves did this, the developers behind the original Shin Megami Tensei IV, and the reception of this major departure has been overwhelmingly positive.

Only a few days ago, I published a review of Pokémon Sun and Moon, and even I can admit that I was harsh on the game. Even so, I don't regret saying what needed to be said, and I feel that despite my vigorous criticisms, I made it perfectly clear that still I enjoyed Sun and Moon quite a lot, and that they had become some of my all-time favorite Pokémon games. It may surprise you, then, to hear that I actually enjoyed Apocalypse way more than Sun and Moon, despite a critique here which was unquestionably and exponentially more scathing. It's just a far better made game.

As part of any other franchise, I may have been a tad more lenient, but giving developers a free pass on this sort of stuff tells them that it's okay to keep doing it, and I'm not going be a complacent in letting that happen here. I respect Atlus as a publisher way too much to, and I empathize with the anxiousness of any fans made nervous by the direction this game went in too much to as well. I know I said that this wasn't a review, and I know that I warned you all not to read this critique without finishing the game beforehand, but I'm sure that more than a few of you read it anyway. So, what do I truly think? Is the game worth playing?

Yes, it is. It's a good game with a lot of flaws outside of just being franchise inauthentic, but it has a lot of heart that will resonate vividly with most fans of the genre. Taken on its own merits, it certainly is the most polished, clean, and ambitious JRPG that I've personally played from this year. But Apocalypse doesn't exist purely within its own merits. It exists, at least partially, from the merits of its forefathers who brought it here, so it also had a reputation to live up to. In that light, it failed gruesomely in nearly every critical regard. I want to remain optimistic, however, that this was just a temporary and experimental detour from the values of the mainline series. Perhaps, with the release of the hopefully inevitable Shin Megami Tensei V, I'll look back at this critique with all of the needlessness of worry that hindsight can sometimes provide. For now, though, I can only dwell on the gruesome.

Playing video games since the age of 5, Spencer Manigat has been fascinated with the possibilities of this interactive medium for nearly as long as he could speak. Recently, his growing obsession with learning about tactile mechanics, interactive narratives, and all things on the academic side of gaming has lit a new passion in him to discuss, debate, and critique various topics in this brilliant medium of video games that we all find ourselves participating in. Pokémon Platinum Version, Super Metroid, and The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker are a few of his favorite games. You can contact Spencer at spencer.manigat@gmail.com or follow him on Twitter @spencewashere.

Playing video games since the age of 5, Spencer Manigat has been fascinated with the possibilities of this interactive medium for nearly as long as he could speak. Recently, his growing obsession with learning about tactile mechanics, interactive narratives, and all things on the academic side of gaming has lit a new passion in him to discuss, debate, and critique various topics in this brilliant medium of video games that we all find ourselves participating in. Pokémon Platinum Version, Super Metroid, and The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker are a few of his favorite games. You can contact Spencer at spencer.manigat@gmail.com or follow him on Twitter @spencewashere.

More Articles

Really liking your reviews. They're simply written, but provide enough information to leave one satisfied. Goodbye metacritic, hello VGChartz :P

Thanks! I'm flattered!

- Spencer Manigat VGC

Very very interesting insight. Thanks for publishing it.

I have not played Shin Megami Tensei games before the last generation (PS3, Xbox360, DS, PSP, Wii), but I became a fan of it when I started playing the Devil Survivor games. I´m trying to dig into the older games slowly since I´ve missed a lot of them.

Shin Megami Tensei is a series that can be highly controversial and may evoke very different feelings from different players. I personally don´t think that SMTIV:Apocalypse is unauthentic to the franchise, since Megami Tensei has so many sub-series and variations and it´s so old that it´s hard to tell what really is authentic to the franchise. I´d say that the only thing that connects all games in this franchise is the fact that you collect and fuse demons and use them to fight. Apart from that, be it character development, plot, settings etc everything can be a lot diverse. I mean... A LOT, specially when compared to Last Bible, Devil Summoner, Persona and Demikids sub-series....

It´s inevitable that, in such diverse universe, certain groups of characters may feel a little off compared to others, but the core gameplay mechanics still provides a good challenge for Jrpgs fans. And, in the end, I think this is what most (of course, not all) fans really are looking for when playing SMT games.

Did I mentioned that you´re doing a fabulous job in Vgcharts with your insights/reviews, Spencer. If not, then let me say now: I appreciate your articles a lot. You´re doing an exceptional job. Have a nice 2017!

Thanks for your kind words! And I was specifically referring to the main series games, excluding all spin offs when I was talking about being "franchise authentic." So the numbered games (SMT I, SMT II, SMT III, SMT IV, and SMT IVA) and arguably Strange Journey since it was originally going to be a numbered entry as well.

- Spencer Manigat VGC